“This isn’t happening. But if it should be happening, it would be alright, so don’t worry, Seymour. It’ll all work out.”

Sara Goldfarb’s early words are a self-soothing affirmation. Her son Harry (Jared Leto) has made off with her television again, pawning it to fund his latest score. When she comes to buy her tv back, the pawnbroker asks her why she doesn’t just finally call the police on her junkie son, her face softens into a maternal embrace. “He’s my only child. He’s all I have.” Her loved ones mean the world to her and devoid of them, Sara is a lone figure, and it hurts. Her journey is one alongside a trio of souls who slip into the monstrous depths of addiction in Darren Aronofsky’s feverish 2000 masterpiece Requiem for a Dream.

Based on the 1978 novel by Hubert Selby, Jr. (who also shares a screenwriting credit with the director), the story follows Sara, Harry, Tyrone (Marlon Wayans, Jr.), and Harry’s girlfriend Marion (Jennifer Connelly) as they succumb to their various addictions and backslide into delusion. While all four stories are harrowing, it is Goldfarb’s story that holds the most fascination because 1) it centers a mature woman, and 2) what she becomes hooked on isn’t often portrayed on the big screen.

Ellen Burstyn is one of a handful of actors to earn the Triple Crown of Acting. Her Oscar came courtesy of Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore in 1975, and three years later she nabbed a Tony for Same Time Next Year. The Emmy would come in the next century, for a 2009 performance on Law & Order: SVU. In an industry rich with a history of putting women over the age of sixty out to pasture, Burstyn has remained booked and busy for over half a century. Charlie Rose, the Exorcist actress hailed the role of Sara Goldfarb as her greatest performance.

Aronofsky and Selby Jr. play a sleight-of-hand with the mother. At first, it seems like her addiction is sugar. As she eats a box of chocolates, she sighs like a user who just got a fix. Her addiction to the television is shot rapid-fire like the heroin-shooting montages: light switch, chair, remote power button, TV synapse. After an unexpected phone call comes, offering to put her on TV, she ambles to her bedroom and pulls out a framed photo of her son’s high school graduation, alongside Harry and her late husband Seymour. She looks upon it with longing and a smile—for the first time, the smile reaches her eyes, it’s genuine. Pulling an old red dress from her closet (the same one she wore in the photo), she tries it on. A relic of a time gone by, the frock strains under her body—time has done what it does to many, adding pounds and a fuller face with every passing year. Her deprivation is palpable.

Her breakfast: grapefruit, a boiled egg, and black coffee. Jump-cut editing emphasizes how unsatisfying the diet is; her food disappears in a fraction of a second with only a single sound of consumption—a slurp of coffee, a squish of grapefruit, a crumble of eggshell. “Your red dress will feel better than a cheese Danish,” she tells herself. It’s a variation on an old thinspiration maxim that’s graced Tumblr shrines to anorexia for years: “Nothing tastes as good as skinny feels.” But it becomes clear that interwoven with intrusive thoughts with food, hungry or satiated, Sara loves the boob tube. It’s television that fills her waking hours, watching Tappy Tibbons (Christopher McDonald) rev up the crowd like a motivational speaker. She dreams of joining him onstage and gaining the love of the audience—and the hearts of America that they represent to her. When she gets the chance to fulfill that dream, she reaches for the one item that reminds her of a time when she was adored by both husband and son. The lack of either in her life causes her a pain so great that she seeks solace, first in the TV, and then in the pills that can help her get camera-ready.

The crash diet is a tale told a thousand times, but Selby’s novel isn’t content to leave it there. Clint Mansell’s tragic theme of stringed arpeggios creeps underneath the dialogue as Sara’s girlfriends talk about dieting. One of them warms Sara up to the concept of diet pills. At first she balks at the idea, but then she begins to see burgers, steaming hot meals, and cupcakes manifesting in her waking hours. She finally gives up and asks for the number of a doctor for a prescription. At the clinic, the doctor comes in and out of the ether, almost a device within Sara’s mind, a mere means to an end.

She is prescribed four pills. Purple in the morning, blue in the afternoon, orange in the evening, and green at night. “Easy as one, two, three, four,” she claims. She doesn’t know what’s in them and doesn’t care. “I’m Sara Goldfarb, not Albert Einstein,” she later scoffs. All Sara knows is that they work, and the pounds are coming off. The drugs give her immediate joy at first—she dances a little jig after one of her first fixes . The joy gives way to hyperactivity as she spends every moment of her day deep-cleaning her apartment. Even when seated in front of the TV, she is jittery, fidgeting with her clothes and displaying a visible sheen of sweat. As the day-to-day repetition of her diet routine descends into addiction, Aronofsky draws the parallel with visuals. In a Debbie Downer version of the Sam Raimi-esque hyper-montage, Sara’s coffee, pills, the zipper of her red dress, and the marker on the scale are juxtaposed with the spoon, the lighter, the bubbling product, and the dilating pupils of her heroin-hooked son.

She develops a tic, grinding her teeth unconsciously. Harry notices on a rare sober visit and, knowing what he knows about certain substances, he confronts her about being on uppers. Why is fitting into that damned red dress so important to her? In a powerhouse monologue, Sara lays it all out. “I remember how he looked at me in that dress,” she says, reminiscing on happier times with Seymour. “Soon, millions of people will see me and they’ll all like me. It’s a reason to get up in the morning, it’s a reason to smile. It makes tomorrow all right.” Harry is utterly distraught, horrified that addiction has touched his own mother. He begs her to throw the pills out and stop seeing the doctor, even going so far as to promise he’ll bring Marion over for dinner and visit more often. Ultimately, Harry remains the same as he has been, leaving his mother alone once again. After his departure, Sara is shot in the extreme right side of the frame, emphasizing the very loneliness she spoke of moments before.

When she does find a moment of solace in her visions of television stardom, the fridge again threatens her high. The waking dreams turn into night terrors, culminating in a drug-fueled fugue state in which she see Tappy Tibbons and a more theatrical, drag-aesthetic version of herself exit the TV and enter her living room, where they both proceed to mock the squalor she now lives in. The live audience joins in on the joke, laughing with the same vicious glee as the prom-goers of Bates High snickering at Carrie White after she takes an involuntary shower in pig’s blood.

In the same Charlie Rose interview, Burstyn expresses that addiction is “about avoiding feeling.” Sara’s pain came from loneliness, and this offer to get her fifteen minutes of fame would remedy that. To get there, she took amphetamines, but she also took them to excise her estrangement from the world. The arc required an actor who could undergo a massive transformation, both physical and mental, and because she had to work from “a really deep place in my psyche, the basement of my being.” Her immersion in the character’s despair shows through all over the 101 minute runtime, but none more intense than in Sara’s most desperate hour.

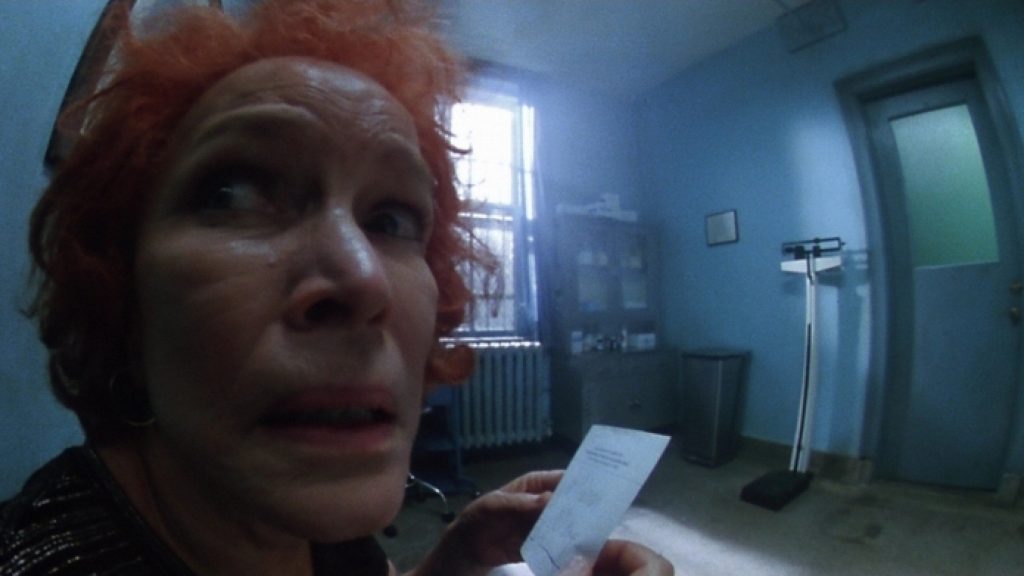

As the widowed mother further descends into delirium, the cinematic eye becomes more distorted. Fish-eye lensing, harness-mounted cameras, and grainy film textures showcase her deteriorating state of mind. After she hallucinates her refrigerator, Sara flees her home and roams along the frigid, snow-covered streets of Brooklyn, raving that she’s going to be on TV. Her hair is grungy and matted, the roots grown out. Her treasured red dress hangs off of her body, the bottom hem filthy with mud and sweat in a devastating testimonial to how far gone she is. Her appearance was one of the most important things in the world to her, and now she is a hot mess.

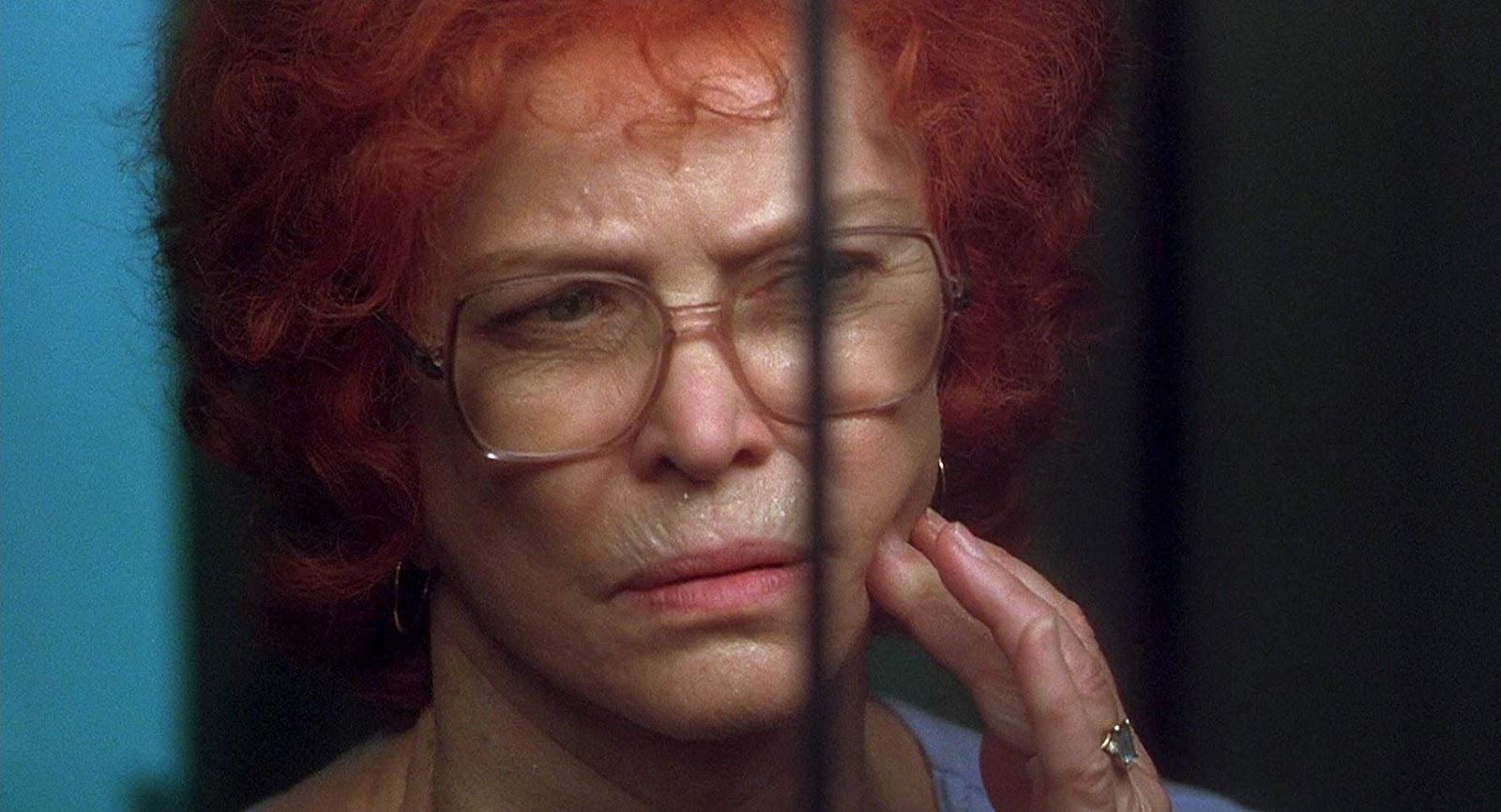

An intervention swoops in after Sara wanders into the office of the agency that originally called her with the offer to be on TV; the receptionist calls the police who, not being medical professionals, drop the tormented, raving woman at a hospital. There, callous doctors give surface-level evaluations without actually engaging with the patient beyond a list of standard questions. She is forced into “treatment,” and given the one thing that she has been willingly depriving herself of in her quest for acceptance and love. Medical attendants restrain her wrists, invade her body with a nasal cannula, and push nutrients into her system as she cries and resists. The doctor, as predatory as any pimp or dealer, takes advantage of Sara’s confusion and gets her to weakly scrawl her illegible signature on a waiver consenting to electroconvulsive therapy. The sequence that follows is one of the most heartbreaking moments committed to film; with Aronofsky insisting upon a tight close-up that refuses to let the viewer look away, medical personnel lubricate her temples, place electrodes on her scalp, and repeatedly deliver electric shocks directly to her head. Despite wearing a mouth guard and having limited movement, Burstyn manages to convey a world of pain and terror entirely through her darting, tear-filled eyes. The American Psychiatry Association calls ECT a “non-invasive process” but it takes mere seconds of witnessing Sara Goldfarb’s torture to see that while her skin is unbroken, her spirit is annihilated.

Sara’s girlfriends Ada and Rae soon pay her a visit in the hospital. Their sighting of her precedes that of the audience, and the utter horror on their faces is familiar to anyone who has lost a loved one to addiction. Their longtime friend is a shell of the vibrant woman she once was. Her hair is raggedly cut close to the scalp, her skin hangs from her frame, and the life behind her eyes is gone, replaced by a deadened gaze into a middle distance that doesn’t exist. In her mind, however, she is a star. The greatest tragedy of Requiem for a Dream is that, after all she went through, Sara is still soothed by the fleeting images on the small screen, dreaming of gliding across the stage in her fitted red dress and embracing her son before the applauding masses. Sara’s final moments before the credits roll are without dialogue, but her lucid gaze and the sounds of Tappy’s show say enough. If she could talk, she’d probably say, “This isn’t happening. But if it should be happening, it would be alright, so don’t worry, Seymour. It’ll all work out.”

“Requiem for a Dream” is now available on 4K Ultra HD from Lionsgate.