THE HISTORY OF SUNBEAM

JOSEPH BLOGGS

IN THE YEAR 1790, the Sunbeam’s fortune was founded by a tinplate plant. From that time until 1937, the last year the skilletmakers kept their identity with the original John Marston Company at Wolverhampton, England, the Sunbeam name was synonymous with quality. Not even Brough Superior, the Rolls-Royce of motorcycles, eclipsed it; the Brough was a product of meticulous screwing together of bought-in components, and Sunbeam, with a few unimportant exceptions, made everything. Scrupulous engineering standards rather than imaginative and forward-looking design was the basis for Sunbeam’s unparalleled reputation.

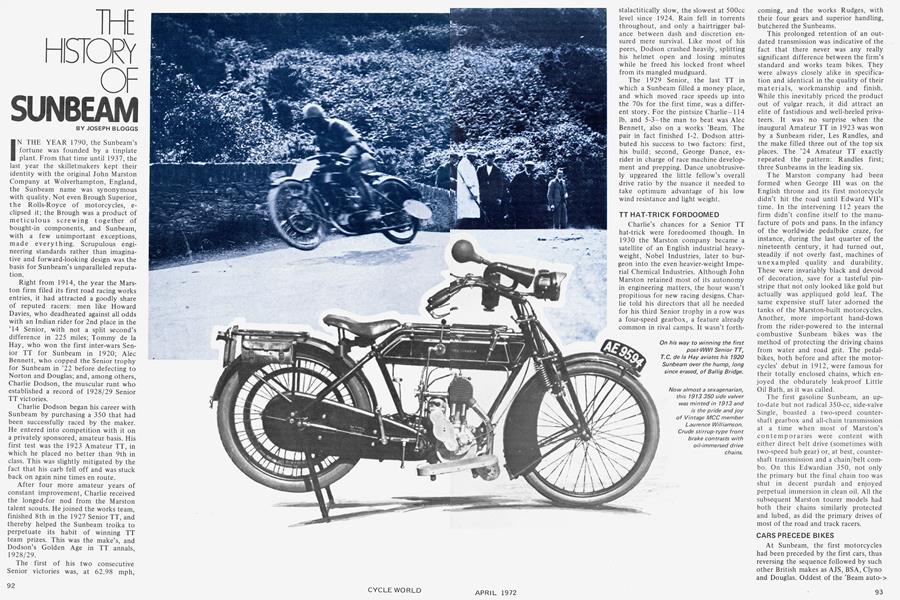

Right from 1914, the year the Marston firm filed its first road racing works entries, it had attracted a goodly share of reputed racers: men like Howard Davies, who deadheated against all odds with an Indian rider for 2nd place in the ’14 Senior, with not a split second’s difference in 225 miles; Tommy de la Hay, who won the first inter-wars Senior TT for Sunbeam in 1920; Alec Bennett, who copped the Senior trophy for Sunbeam in ’22 before defecting to Norton and Douglas; and, among others, Charlie Dodson, the muscular runt who established a record of 1928/29 Senior TT victories.

Charlie Dodson began his career with Sunbeam by purchasing a 350 that had been successfully raced by the maker. He entered into competition with it on a privately sponsored, amateur basis. His first test was the 1923 Amateur TT, in which he placed no better than 9th in class. This was slightly mitigated by the fact that his carb fell off and was stuck back on again nine times en route.

After four more amateur years of constant improvement, Charlie received the longed-for nod from the Marston talent scouts. He joined the works team, finished 8th in the 1927 Senior TT, and thereby helped the Sunbeam troika to perpetuate its habit of winning TT team prizes. This was the make’s, and Dodson’s Golden Age in TT annals, 1928/29.

The first of his two consecutive Senior victories was, at 62.98 mph, stalactitically slow, the slowest at 500cc level since 1924. Rain fell in torrents throughout, and only a hairtrigger balance between dash and discretion ensured mere survival. Like most of his peers, Dodson crashed heavily, splitting his helmet open and losing minutes while he freed his locked front wheel from its mangled mudguard.

The 1929 Senior, the last TT in which a Sunbeam filled a money place, and which moved race speeds up into the 70s for the first time, was a different story. For the pintsize Charlie—114 lb. and 5-3—the man to beat was Alec Bennett, also on a works ’Beam. The pair in fact finished 1-2. Dodson attributed his success to two factors: first, his build; second, George Dance, exrider in charge of race machine development and prepping. Dance unobtrusively upgeared the little fellow’s overall drive ratio by the nuance it needed to take optimum advantage of his low wind resistance and light weight.

TT HAT-TRICK FORDOOMED

Charlie’s chances for a Senior TT hat-trick were foredoomed though. In 1930 the Marston company became a satellite of an English industrial heavyweight, Nobel Industries, later to burgeon into the even heavier-weight Imperial Chemical Industries. Although John Marston retained most of its autonomy in engineering matters, the hour wasn’t propitious for new racing designs. Charlie told his directors that all he needed for his third Senior trophy in a row was a four-speed gearbox, a feature already common in rival camps. It wasn’t forthcoming, and the works Rudges, with their four gears and superior handling, butchered the Sunbeams.

This prolonged retention of an outdated transmission was indicative of the fact that there never was any really significant difference between the firm’s standard and works team bikes. They were always closely alike in specification and identical in the quality of their materials, workmanship and finish. While this inevitably priced the product out of vulgar reach, it did attract an elite of fastidious and well-heeled privateers. It was no surprise when the inaugural Amateur TT in 1923 was won by a Sunbeam rider, Les Randles, and the make filled three out of the top six places. The ’24 Amateur TT exactly repeated the pattern: Randles first;

three Sunbeams in the leading six.

The Marston company had been formed when George III was on the English throne and its first motorcycle didn’t hit the road until Edward VII’s time. In the intervening 112 years the firm didn’t confine itself to the manufacture of pots and pans. In the infancy of the worldwide pedalbike craze, for instance, during the last quarter of the nineteenth century, it had turned out, steadily if not overly fast, machines of unexampled quality and durability. These were invariably black and devoid of decoration, save for a tasteful pinstripe that not only looked like gold but actually was appliqued gold leaf. The same expensive stuff later adorned the tanks of the Marston-built motorcycles. Another, more important hand-down from the rider-powered to the internal combustive Sunbeam bikes was the method of protecting the driving chains from water and road grit. The pedalbikes, both before and after the motorcycles’ debut in 1912, were famous for their totally enclosed chains, which enjoyed the obdurately leakproof Little Oil Bath, as it was called.

The first gasoline Sunbeam, an upto-date but not radical 350-cc, side-valve Single, boasted a two-speed countershaft gearbox and all-chain transmission at a time when most of Marston’s contemporaries were content with either direct belt drive (sometimes with two-speed hub gear) or, at best, countershaft transmission and a chain/belt combo. On this Edwardian 350, not only the primary but the final chain too was shut in decent purdah and enjoyed perpetual immersion in clean oil. All the subsequent Marston tourer models had both their chains similarly protected and lubed, as did the primary drives of most of the road and track racers.

CARS PRECEDE BIKES

At Sunbeam, the first motorcycles had been preceded by the first cars, thus reversing the sequence followed by such other British makes as AJS, BSA, Clyno and Douglas. Oddest of the ’Beam auto-> mobiles was the Sunbeam-Mabley, “whose inspiration,” according to a leading British engineering historian, the late Jim Sheldon, “was probably the long forgotten Victorian S-sofa.” This creepabout, dating from 1901, afforded entry/exit for driver and passenger on opposite sides of the body and incorporated a curvacious central division, S-sofa fashion, between the active and passive motorists. Viewed in plan, the Sunbeam-Mabley was diamond shaped rather than rectangular, with two of its wheels amidships, at about the plane of the occupants’ elbows, and the other two front and back but on the longitudinal centerline.

The firm’s elevation to the ranks of legitimate car makers more or less coincided with its enlistment of the famous French designer of ground vehicles and aircraft, Louis Coatalen. He created all time’s biggest and most powerful British bidder for the Land Speed Record, the 48-liter, 4000-horsepower Sunbeam Silver Bullet, which—out of character for Coatalen-proved a total and costly flop, as it attained speeds not greatly in excess of yesteryear’s Sunbeam kitchenware.

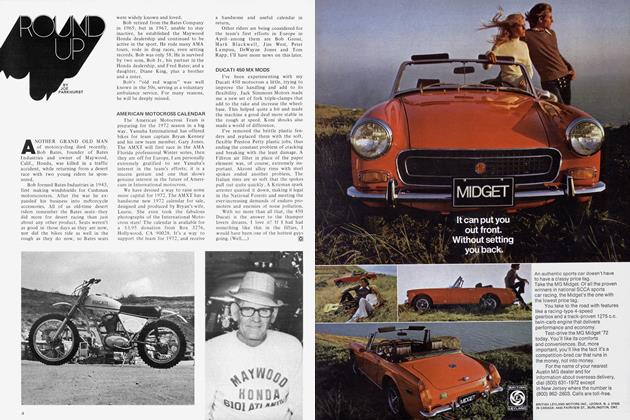

J.E. Greenwood, formerly chief designer at the JAP motorcycle engine factory in London, drafted the 350-cc forefather of the John Marston bike range, and in 1913 came up with two new ’Beams. Both were sidevalvers, a 500 Single with a shortish stroke (88 millimeters) and effectively an overgrown edition.of the 350, and a V-Twin of around 750cc for sidecar hauling, powered by one of his JAPs. Both models carried on the Little Oil Bath tradition, had a three-, instead of twospeed transmission, and, with their quickly detachable rear wheels, went far towards licking one of the worst and most frequent roadside chores of the day—repairing tire blowouts and punctures.

Greenwood’s 1913 500, which was standard apart from a slightly lowered engine mounting, a separate engine oil supply in a tank hung from the saddle tube, and foot and hand brakes both operating on the back wheel, carried Howard Davies to his 1914 Senior TT deadheat in the marque’s first road race.

Sunbeams of various calibers, including a JAP-powered V-Twin of 1000cc displacement, served the armies of several Allied nations during WW1. Alternatives to the original JAP powerplant in the V-Twin were, at various dates, the Swiss M.A.G. and the Abingdon King Dick, which was British.

The one that had started it all, the 3 50, dropped from sight in 1915, leaving two variations of the side valve 500 to carry on the one-lunger line after the war. These bikes were backed up by the two-lung sidecar hauler. A Light Solo derivative, disguised for its Isle of Man role by lowered bars and rear-set pegs, was also offered, and one of these freighted Tommy de la Hay to his 1920 Senior TT victory. What’s more, he won by the startling margin of 3 min. 52 sec.

The fashion among bhp seekers at that time was to stretch strokes at the expense of bores, contrary to today’s practice. Oddly enough, where other factors were equal, the recipe often seemed to work. A classic case in point was the history-making Long Stroke Sunbeam described by historian Sheldon as “. . . the best side valver ever produced.” In general design its 499-cc engine closely resembled the shortie it superseded, but its stroke was lengthened from 88 to 105mm. Launched in 1921, it immediately established itself as the fastest 500 on the British or any other market.

THE "LONG STROKE" A FAST 500

Concerned only in making its machine as functional as an ax, the Marston drawing office stuck to science and disdained art. Thus, the Long Stroke’s tank toptube sloped slightly downward towards the low steering head, conspicuously out of parallel with the exhaust pipe, which had an opposite incline. Also eye-catching, though in an attractive sense, was the induction plumbing. The straight and truly horizontal inlet pipe was matched by an attenuated air intake. The combined lengths of the two tracts was not far short of one foot.

The Long Stroke’s brakes were of the dummy belt rim type, and like all other Sunbeams since 1912, the bike had its magneto located behind the cylinder. Setting a new fashion, the rectangular toolbox was attached to one of the lower rear frame members.

The special Long Strokes raced in the TT of 1922 had non-standard pistons (aluminum alloy replacing iron), a mechanical oil pump with pedal-operated auxiliary pump for high stress conditions, a close ratio gearbox (still three speeds), and a tankside shift lever set at the characteristically Sunbeam angle. This machine won the second of Sunbeam’s four Senior TT conquests, and for winner Alec Bennett, breaker of both the local race and lap records, it was a personal triumph.

Although he was a relative newcomer to road racing, Bennett had an unseen ace up his sleeve. Back home on the half mile tracks of British Columbia, he’d acquired a seventh sense in pointing his bike into impenetrable clouds of dust and keeping everything wound on. He put this experience to good use in the TT, as the Manx roads were untarred and almost as dusty as the Canadian ovals he’d ridden in his teens.

His stretch on the Sunbeam factory team coincided with its total half-liter international supremacy, and he confirmed his Campionissimo rating by > cleaning up the French Grands Prix of 1921 and ’22.

The death of John Marston himself in 1918, and of his son Roland the following year, had little effect on the company’s staunchly conservative policies, for the new chief, Sidney Bowers, was equally if not more conservative. Sometimes, too, there was an illogical element in the board’s decisions. Scaling up Greenwood’s original 350 to make a 500, and then scuttling it just when it was ripe for further development, is an example of this.

The firm’s conversion to overhead valves was a three-phase process. George Dance, the uncrowned king of Britain’s hillclimb and flat sprint courses, set the ball rolling in or around 1922 with an engine combining the side-valve 350’s bottom end with an experimental head containing vertical overhead valves. In 1923, all-new pushrodders with inclined ohv and hemi heads were readied for the works team, but only the smaller of the two, a 350, was fielded in the TT. The larger 493-cc edition sat the Senior out in favor of the already proven Long Stroke.

Phase Three in 1924 saw ohvs in both 350and 500-cc sizes. Those were known as Models 8 and 9 respectively. Mechanically identical, but much easier on the eye, were the alternative Sprint ’Beams known as Models 10 and 11. These featured small-capacity, wedgeshaped tanks and rearward sloping upper frame tubes that answered the aesthetic objections to the traditional Sunbeam bone structure.

Early versions had inclined pushrods and triple concentric valve springs, but these were later superseded by parallel rods and the hairpin springs (unobstructive of airflow to the valves) that became part of the Sunbeam engineering legend. Single and twin port heads were available at option and, in either case, the finning around the exhaust port was conspicuously deep. For racing, the double spout was favored, and in this form the Model 8 became the 80 and the 9 the 90.

SUCCESS FOR THE "ROCKERBOX”

The extent of these rockerbox Sunbeams’ success in every kind of speed event was practically limitless. At opposite ends of the spectrum, George Dance broke the 500cc world standing start record in 1923, and the following year became the first rider ever to beat an 80-mph average for one hour on a 350. In 1925 and ’26, French independents won the 24-hour Bol d’Or on Model 90s. On the first of these occasions, Francisquet covered 1004 miles “in spite of a serious accident,” and without benefit of a relief rider. One could add that the circuit, with its atrocious surface and cambers, was a serious accident in itself.

In 1925 John Marston put some of his eggs in an overhead camshaft-type basket and then let them drop out through a hole in the bottom. Thereby hangs a tale of unaccountably unfinished business. The ohc engines, built in 500and 600-cc sizes for the Senior and Sidecar TTs, but with a common bore measurement, had vertical shaft drive to its single camshaft. It also featured hairpin valve springs, dual exhaust ports and dry sump lubrication. Otherwise, it was much like the current pushrodders. Being new and relatively undeveloped, though, it wasn’t 100 percent reliable. Graham Walker, the works team’s chief hope, was disputing 3rd place in the Senior TT when a wrist pin end pad pulped and he had to quit. Graham’s chances looked good too in the sidecar event, until his mag control wire snapped.

Discouraged on such slight grounds as these, Sunbeam abandoned its ohc endeavors, just at a time when its important rivals in the industry were espousing the principle, or would shortly do so.

John Marston, fortunately, didn’t hasten to scrap his tiny treasure of ohc engines. At least one found its way into private ownership and, in 1927, R. Gibson rode it to victory in the 500cc class of a major Brooklands classic.

In 1923 the big Twin sidecar bike, which never enjoyed the same supremacy in its class as the 350 and 500 Singles had in theirs, was replaced by an up-stroked, side-valve Single, the socalled “414.” A plonker par excellence, it responded quite rewardingly to the renowned tunecraft of George Dance. With the aid of a pair of improvised reins, he was able to walk unhurriedly alongside it and its occupied sidehack. This demonstration of flexibility was later independently emulated by one of Motor Cycling’s road testers. In 1925 the same magazine timed a single-port ohv ’Beam 500 at 84 mph and was enthused over its “exceptionally effective brakes and unique adjustable clutch stop.” The purpose of this clutch stop was to prevent the cork-faced plates from dragging after the machine had been left standing, and also to facilitate pauseless shifts. Cork as a clutch material, obviously more vulnerable to heat than alternative compounds, was retained by conservative Sunbeam long after the competition had made a switch.

NEW FRAME: BRUTAL HANDLING

Regarding frame design: Sunbeam was neither more nor less receptive to new ideas than most of its British contemporaries. For the first 26 years the clientele, whether it liked it or not, was stuck with what it affectionately called the' bedstead frame. After all, what harm had a bedstead ever done anybody? But in the winter of 1928, following the current trend, Sunbeam ditched Old Faithful, with its long-reach riding position, forward downsloping toptube and short steering head, and took a great leap forward. The new frame with its big-diameter, tankenshrouded single toptube, shortened wheelbase, and much lengthened head, offered a more comfortable riding position, but didn’t do much for handling and road holding. The fact is, the new-look 80s and 90s were pretty brutal handlers. Dodson, notably, and others less notably, handled them successfully at speed, but it took a determined effort.

(Continued on page 144)

Continued from page 96

Marston Sunbeams also made a great name in trials, in the days when these were as much a test of reliability as trick riding. In national classics of one-day and half-day length, they were consistently a force to be reckoned with, and repeatedly served their country with honors in the International Six Days. As Sir John Vanbrugh had said, glimpsing the obvious, “Quality always distinguishes itself.” Speaking of quality, John Marston people were jealous of their fabled standards of finish, and enamelwork in particular. On one pretext or another, visitors to Sunbeam were quietly given a steer around the department where that inimitable black and gold gloss was imparted to tanks, frames, and mudguards.

The literature of the Sunbeam was a standout too. It was lucid, copious, and almost comically comprehensive. The Book of the Sunbeam, elaborately illustrated with line drawings, diagrams, cutaways and photographs, contained indirectly relevant sections on driving, license procurement, insurance, riding clothes, club membership, hand signaling, skid correction, roadside signs, and gave a detailed exposition of Herr Otto’s four-stroke cycle. There were minute instructions for such advanced exercises as total dismantling, overhaul, and reassembly of the gearbox. Naturally, there was a strong fraternal bond among devotees of so characterful a make, and this, in or around 1923, found expression in the formation of a club, the Sunbeam M.C.C. Three years later this nationally renowned body abandoned its exclusivity and accepted owners of any make as members.

MERGERS AND EXTINCTION

Gradually, and somewhat to the distaste of longtime idolators of the Marston ideal, the Imperial Chemical Industries’ influence began making itself felt during the Thirties. There was, to be sure, no perceptible slackening of the old standards of quality, but chromeplated gas tanks introduced a painfully anachronistic touch to the exterior decor. Engineering developments around this time included the addition of two 250 models, one a high camshaft pushrodder, the other a road race aspirant with a rather antique bore/stroke ratio—59 by 90mm. This, the Little 95, never made its intended mark, however.

Also in the Thirties, the firm became weight conscious, parting its range down the middle into lightweight and heavyweight divisions. The former included 250-, 350and 500-cc models, while the heavy division consisted of the time tested Long Stroke ohv 500s in various stages of potency and a side-valve 600 for sidecar work. Sporting versions of the lightweights gave the Sunbeam tradition another sock in the eye with blue tanks.

The blackest day, though, came in 1937 when Wolverhampton’s association with the ne plus ultra motorcycle was severed and Sunbeam moved south to Plumstead, London. There they joined Matchless and AJS under the Associated Motorcycles umbrella. Some criticism followed, but it’s only fair to say that the bikes that carried the Sunbeam badge from 1937 through ’45 were still of excellent quality, even if they lacked the individuality of their Wolverhampton forebears.

The final chapter of the story begins shortly after World War II, when BSA acquired the Sunbeam name from AMC and, for most critics’ money, there was only one thing wrong with the bikes that came in the wake of this deal: misuse of the Sunbeam label. The closely related S7 and S8 machines gave a new meaning and validity to the term “badge engineering.”

Designed by Erling Poppe, a veteran of the English sprint courses, the S7 and S8 were 500-cc vertical Twins with their oversquare (70 by 63.5mm) aluminum alloy cylinders in line-ahead formation. They also had integral four-speed gearboxes, fully balanced cast iron crankshafts, and shaft final drive via underslung worm gears. The two models differed only insofar as the S7 tourer had in-line valves, canted at 22 deg. from the vertical, against the more sprightly S8’s 90-deg. valves in hemi combustion chambers. Camshafts were overhead and chain driven, and the numerous shared refinements included a strictly non-varicose engine lubrication system (all oilways internally formed) and a plunger-mounted saddle with wick lubrication.

Former works rider Graham Walker, who had become editor of Motor Cycling, wrote of the S7: “It starts first kick . . . idles like a gas engine ... is completely devoid of transverse torque . . . has brakes equal to its magnificent steering qualities, [and offers] performance which is deceptive because of its very smoothness.”

So what was it, then, that foredoomed this paragon to extinction. Could it have been that apple green tank and mudguard paint job?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue