David Nebreda’s work changed my life. It’s no mystery. I remember the first time I encountered his photographs (or they encountered me): it was in a sort of catalog – David Nebreda: Autorretratos (2002) -, that followed one of the author’s rare solo exhibitions, curated by Javier Panera, during the celebrations of the European Capital of Culture in 2002 (Salamanca). In addition to disturbing and revealing, the experience of this first encounter with the work of Nebreda evoked a series of emotions that I was associating with the notion of truth and that triggered a personal odyssey with the idea of authenticity, that was then explored both during my masters and PhD (and was actually at the core of Nihilsentimentalgia). Curiously, in the first pages of that catalog, Panera describes the moment he encounters Nebreda’s photographs, stating the term that had occurred to him then was Ecce Homo, in its literal translation: Behold the Man, David Nebreda materialized on the sign of his pain. Panera’s bewilderment echoes the daze that still qualifies my relation with two themes: Nebreda and authenticity.

I find it particularly difficult to write about the things I love the most, so I’ve been postponing this text for years now. I considered writing it in my mother language, to make it easier, but that doesn’t really make sense in Nihilsentimentalgia. This love-hate relationship with the experience of Nebreda’s art manifested itself a number of times. During my masters, although Nebreda’s work was at the core of the theoretical work, I managed to avoid writing about his work. By the end of my PhD thesis, something similar was repeating itself. Two months before I handed in the work, I decided to face the dragon and deal with the subject. What I’d like to make public here, now, is a resume of that experience.

During my investigation of authenticity, what I always wanted to suggest is that authenticity is an artistic quality and, in that sense, one should be able to recognize it in a work of art. Applying that premise to Nebreda was particularly challenging, for I’ve read everything he ever published, so I’m unable to talk about his work without referring to his biography. David Nebreda was born in Madrid, in 1952. He suffers from schizophrenia and that’s all I want to mention here.

In fact, Nebreda’s biography seems to have all the necessary ingredients to catalog him as a marginal artist and to make his art a success in the ‘outsider art‘ market. If some circumstances were different, maybe today Nebreda would be just another addition to the list of artists at the famous Outsider Art Fair, held annually between Paris and New York. However, Nebreda’s truth and lucidity, as well as the honesty of his publisher Léo Scheer, seem to have been decisive in removing his work from a sensationalization that was easily discerned and recognized by himself when describing the impact of his first show as a phenomenon both unforeseen and expected.

In the four phases reproduced in Autoportraits – the first book published by Léo Scheer, in 2000 – we find multiple registers: there is a central theme, which can be understood as the substitution of the individual for a photographic other – the self-portrait; a central plastic form, where we emphasize the use of black and red; a rigorous geometric construction; a primary set of signs, marked by a preponderant minimalism; a mimetic strategy evocative of the appearance of the divine; and, finally, the inclusion of texts in the images, suggesting that the work is revealed (also?) by means of an understanding of these words, that we can read as clues. However, if the observer persists in regarding Nebreda’s work as if there were a cognitive and moral purpose to it, one will soon be trapped in the literary references. As I see it, if there is a truth that guides Nebreda’s art and emancipates itself from the mimetic dimension, that truth seems to concern self-portraiture.

I believe Nebreda’s self-portraits indicate a split that prevents the author from recognizing the difference between body and spirit (or, as Nebreda would say, between body and brain). Knowing that Nebreda suffers from schizophrenia is an important fact, not because this information must in itself condition our relationship with the work, but because it allows us to better frame a great part of the symbolic universe found in his art, which would otherwise appear without context. It is Nebreda himself who tells us that his work should not be understood as a document illustrating his condition as a sick person, but rather as a work with aesthetic qualities that guarantees it artistic autonomy. It is not a matter of transforming the schizoid entity of Nebreda into a biographical anecdote, nor of looking at his work as if it were a pathological record, rather one that is concerned with the way in which schizophrenia accentuates the biological condition of the experience of limits that Nebreda explores in his work. However, what continues to affect me in Nebreda’s work is precisely what he refers to as true image.

The ideas of nil and death that guide the artistic project of Nebreda are universal themes. As is made clear in Autoportraits, Nebreda was interested in the concept of death, but this concept disappeared as soon as he was confronted with the very real imminence of his own death, moment from which he dedicated himself to the creation of a new identity – the mirror-object – which through a photographic other allowed him to think of himself as a living entity. In the second photographic period, it is possible to recognize the complete identification of Nebreda with the foreshadowing of the “invasion” of the disease, which the author chooses to describe as an unavoidable nothingness, a “daily hell of radical and profound denial of self”. This absolute negation, which forms the core of Nebreda’s work between 1989 and 1990, composes the delirious scheme of his schizoid personality, leading us to believe that in some of the self-portraits of this second period the truth is exposed through the sacrificial act that is the delivery to that vortex, the nil.

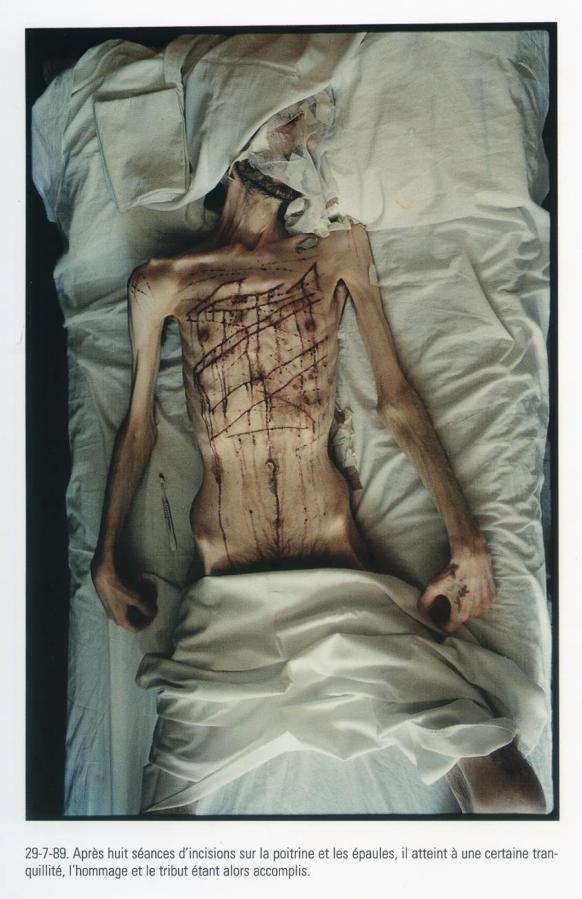

One of the images that alludes directly to this sacrificial act shows us a skeletal body, with a veiled face, a mutilated upper-body, lying on a bed dressed in white. In this photograph, the body is a screen for death, it is the brush-made scalpel that opens that slit to nothingness. In the caption we read: “29-7-89. After eight sessions of incisions on the chest and shoulders he attains a certain tranquility, once the homage and the tribute have been fulfilled”. In the representation of this violated body, there’s the true image of a Being who, in an attempt to prevent the “invasion of his brain”, seeks to be replaced by a photographic other. It is through his imagery that both the self and the other acquire the necessary autonomy to survive. It’s about the revelation of a dimension of human suffering that is kept in the dark, but which, once brought to clarity, confronts us with something that we recognize as essential.

It’s not like the encounter with Nebreda’s work is also my first confront with the representation of human suffering. In photography, one is (too) frequently confronted with the representation of catastrophe and pain. But when we speak of those instantaneous registers of the suffering of others, I don’t think we’re addressing works of art. But what distinguished Nebreda’s imagery then? I suggest that, in a way, there is a human dimension that we inhabit that is essential to us, that guides our action, and that his work unveils. In fact, it is Nebreda who tells us that “unveiling allows revelation to be recognized; it is the hidden truth that exposes all that was lacking to the absolute … since what matters is that the amorphous matter of revelation which always bears the trace of reality, of future, of hope, that which always transforms or gives form, becomes truth”. Thus, what seems to distinguish Nebreda’s work is the fact that it reveals the struggle of wanting to enter the realm of life.

As there is death, pain, vertigo, violence and hallucination in Nebreda’s work, there is also life and the revelation of something that, although transformed into art, preserves a personal dimension. But seeing, feeling, experiencing, understanding or analyzing the work of David Nebreda always implies recognition of the violent character of the self-portrait. Many of those who come into contact with his work may be tempted to attribute that violence to an ideological and/or symbolic value that inevitably refers to bodily performance, masochism and eschatology, in short to the unidimensional representation (and often superficial) that leads us to associate pleasure with pain. However, any analysis, however brief, of Nebreda’s work will naturally prove the marginal importance of these references. Nebreda himself, when confronted with the analogy to body art, does not hesitate to condemn the plastic, frivolous and superficial compliment that “these artists” make of the body, arguing that what he seeks is “an anterior point to the experience of pain or pleasure” and that in his case there is no distance between what is Man and what the body of Man is, but rather an experience of being-itself, that has no limits. But to make sense of Nebreda’s self-inflicted pain is no simple task. As he himself explains, his “bloody skeleton” is not only a “collective organ” but also a “predefined symptom”. Many of his photographs are received with a repulsion that immediately equates them with something immoral or false (as a record mechanism of self-flagellation). However, although bloody and amputated, I find in those very same registers a dimension of truth that refers us precisely to the idea of what is necessary, although at times technical execution may confine the work to a merely indexial status, robbing it of a certain dynamic and depth that we recognize in other works.

For me, the punctum in Nebreda’s art does not pertain to self-flagellation or the representation of that self-flagellation, since in the encounter (between the observer and the images) one does not even recognize that body as the body of a particular individual, in which we project concrete stories and feelings. On the contrary, in that body we recognize the essence of all bodies that want to breathe and whose sigh always keeps at the same time a harbinger of death and life. According to Lacan’s theory of the formative function of the stade du mirror (“mirror stage”), there is a separation that occurs naturally in children, which leads them to compartmentalize the physiological body and the mental body, but in Nebreda that function seems to have failed its purpose. Instead, in his images it is possible to identify a pathological relation with the mirrors, and the magnetic field constituted between his body and his mirrored image seems to have a regenerative function. For example, in one of his self-portraits in the mirror we find the following legend: “The discovery of the true meaning of the mirror. He no longer knows where he is and where the other is.” But it is not the experiences of death, of pain, of nothingness or of rebirth, alone, that guide the experience of limits to which Nebreda submits his work. Admitting that, as he himself affirms, his work follows the principle of ce qui est necessaire (“what is necessary”), the experience of being seems to obey an urgency that the spirit imposes on the body, and I think it is precisely that “urgency” that potentiates the dynamics of the work in the path of truth.

In one of the more complete essays about Nebreda’s work, by Jacob Rogozinski, the author begins by describing one of Nebreda’s most disquieting self-portraits – Face covered with excrement – and he states: “Why do I have the impression that this face without eyes, this garbage-face, is staring at me? That everything Nebreda does, his photographs, his drawings, his texts, are intimately connected to me and strike me at my utmost inner self – that all of that regards us?” Like Rogozinski, I find in that face covered with excrement a dialogue between originality and technique that marks the style of Nebreda, as well as a dynamic between truth and soul that marks the autonomy of the work. I do not deny there was a moment of shock when I first saw that image, but what the work reveals beyond that is that there is an iconic, universal value in the representation of waste that concerns all of us. By the way, in Autoportraits, waste is almost a theme. As I understand it, it is the ultimate mark of the subversive character of Nebreda’s work, insofar as it profoundly denies the ideal of beauty and (moral) good in art. They are what we do not see and do not want to see, at the same time awakening in us the recognition of a truth, about our condition.

When asked about the profound effect of Nebreda’s art, Rogozinski evokes the Kantian sublime to tell us that the “dark and creepy beauty” he finds in Nebreda’s works is a beauty of the order of the unsustainable, thus exposing the impossible, testing the limits of what it reveals. On the other hand, Frédérick Aubourg (2002), rehearsing a Freudian analysis of Nebreda’s work, identifies “the mode of production of images” as “the particularity of Nebreda’s photographs”. In other words, it is in Nebreda’s way of doing that Aubourg locates the singularity of the work, both “in the technical conditions” of the work and “in the place that this practice occupies for the author”. Nebreda’s “project of regeneration” creates a second life, with new conditions, new spaces, new rules. According to Aubourg’s analysis, Nebreda’s photographs “wound us” because we recognize in them the limit of life and the experience of death. However, recovering the words of Nebreda when he tells us that what he seeks is “a point before the experience of pain or pleasure”, I suggest Nebreda’s way of doing art is also a way of recovering an identity that is both his and ours, for his work confronts us with the possibility of authenticity.

One thought on “Nebreda: my everlasting love”