Doing Business in the Shadows

The black market thrives throughout the Islands. Here’s how much people make in three local underground industries: cockfighting, prostitution and marijuana dealing – and why they do it, despite the risk of arrest.

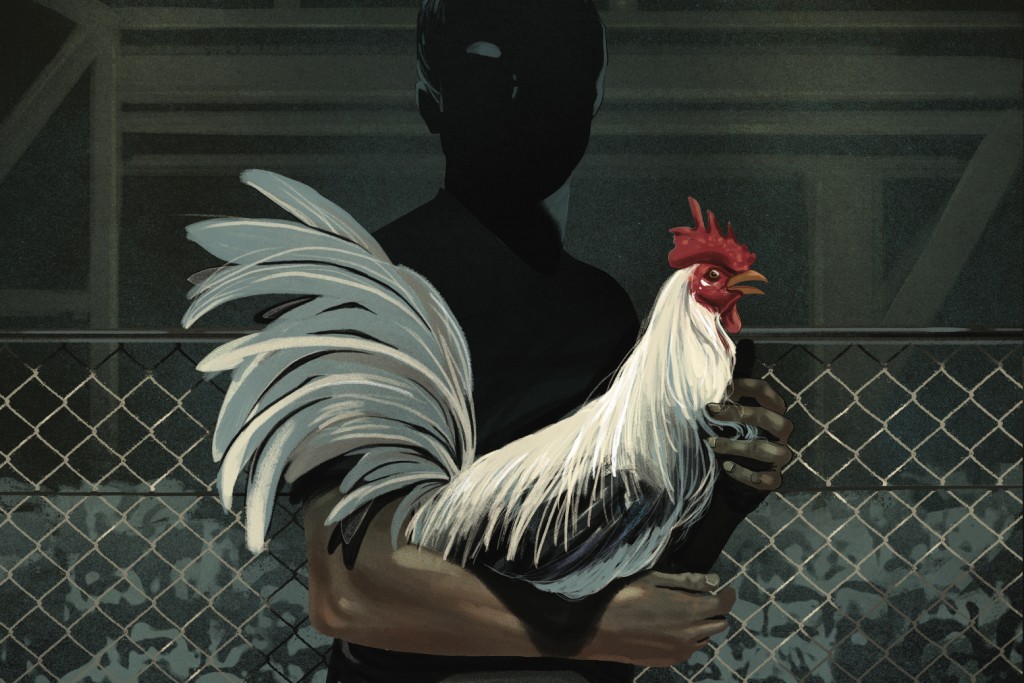

Tonto pulls down his black beanie and walks under the carport of a two-story house tucked in Waianae’s Lualualei Valley. He joins two men huddled in one corner and holding a small, black rooster. Extending the rooster’s right leg, the older of the two men quickly wraps the leg with red ribbon. From a small wood box, he pulls a curved, three-inch blade – known as a knife or gaff – and meticulously attaches it to the rooster’s spur with dental floss. Once it’s secure, he sheaths it and hands the rooster to Tonto.

Tonto takes the bird into a nearby 30-foot ring made from sheet metal, joining a serious man with a shaved head holding a multicolored rooster. A crowd of men, women, even teenagers and children, press against the ring’s chain-link fence. Many shout bets at each other as Tonto and his opponent remove the blade covers. They square up, shake hands, then squat down and release their roosters. The birds kick with their knifed legs, frenziedly flap their wings and peck each other’s necks, as their handlers scuttle around. In less than two minutes, both birds are too injured to stand, but still alive. The fight is a draw. Tonto gently picks up the limp, bloodied bird. He returns to his chair outside the ring, drops of blood on his crisp white T-shirt.

In his mid-60s, Tonto has been a cockfighter, or cocker, since he was a teenager. Tonto isn’t his real name, but it’s how most people know him. His favorite pastime, and a prime source of his income, is part of a vast underworld economy that thrives across the Islands.

The economic effects of the black market, also known as the shadow or illegal economy, haven’t been widely studied in Hawaii, says UH economist Carl Bonham, so it’s diffcult to determine its reach. Nationally, a 2012 study by University of Wisconsin- Madison economist Edgar Feige estimated that black market activity totaled $2 trillion a year in the U.S. That number is likely higher today.

But it doesn’t take an economist to point out that for many kamaaina, cockfighting, gambling, prostitution and drugs are just as ingrained in Hawaii life as plate lunches, surfing and aloha wear. The shadow economy isn’t just obviously criminal activity; it also includes actions that otherwise law-abiding people frequently do: pay cash for services, knowing the contractor is likely not report- ing the income or paying taxes on it, or contracting unlicensed tradespeople. Many people operate completely in the black market, despite the risks of arrest, stigmatization and injury. Here are the stories of four kamaaina who work in Hawaii’s shadow economy, how much they make and why they do it.

Cockfighting in the Country

Born and raised on Oahu’s leeward coast, Tonto is a short, soft-spoken man who laughs a lot. He’s been around chickens virtually his entire life. From a big Filipino family, he helped raise the birds and first watched his relatives fight them starting when he was 5. “When (my grandparents) would get mad at each other, they would settle it with chickens,” he says. When he was a teenager, he competed in his first cockfight in an uncle’s back- yard. He won $10.

There are three main positions in cockfighting and Tonto is experienced in each. (That’s why he was asked to fight the black rooster at the Waianae fight, even though it wasn’t his bird.) There’s the rooster trainer, the heeler, who ties on the knife, and the pitter, who releases the bird inside the ring.

The fact that cockfighting is illegal doesn’t bother him. He’s been caught by police 25 times at cockfights, as a heeler and pitter. In Hawaii, cockfighting is a misdemeanor; if convicted, the maximum sentence is one year in jail and up to $2,000 in fines. The illegal gambling so intrinsic to the sport is also a misdemeanor. (In 2015, Hawaii legislators introduced a bill that aimed to make cockfighting a felony, but it didn’t pass.) In 2016, Honolulu police narcotics/vice officers made three arrests for cockfighting, and nine for illegal gambling.

Tonto has spent a year in prison for the illegal sport. “When I was in jail, I was drawing roosters, I was reading about them. Right after I got out, that weekend I was fighting.”

Tonto says today he owns 15 chick- ens, breeding and raising them in his small backyard farm in Nanakuli. Many cockers consider themselves chicken aficionados and spend years perfecting their breed’s bloodline.

“I raise pure white birds,” he says, adding that he names them. “They’re my babies. I spend more money on the chickens than I do on myself.” They are stately roosters with thick legs and flowing breast feathers that resemble a silky mane.

Serious cockers are proud of their roosters and, because of the high stakes in their sport, they spend exor- bitantly on the birds. They buy only top-shelf feed. Tonto says a 50-pound bag costs $30, and only lasts a week.

“The important thing in the gamecock world is the health. If they’re not healthy, you’re half a loser already.” Cockers also give their birds supplements, including vitamins, adrenaline, caffeine, even strychnine, all of which cost a couple of hundred dollars a month.

Tonto says he only gives his birds amino acids and B12. “Back in the old days, they didn’t give any chemicals to the chickens. If he was a loser, we’d take him home and cook him. Back in the old days, they never wasted anything. Now it’s hard because (fighters) use so much chemicals to get the birds ready for fights.”

It takes two weeks to get a bird fight-ready, says Tonto. Each rooster is tethered to a wood teepee in his backyard. During their conditioning, they’re moved roughly every day to his fly pens, where they fly up and perch, and scratch boxes with straw to work their legs. “Chicken raising is 24/7.” One of Tonto’s close friends in Waianae has a similar layout, but for 200 birds; another cocker in Waimanalo has more than 500.

This is all preparation for the gamecock’s only purpose: fighting. For bird owners, cockfights are not only to showcase their breeding and training skills, but to recoup costs, even make profits. Nearly two hours before the Lualualei Valley fight began, the day’s fighters stood around, a Heineken in one hand, a cigarette in the other, talking story about last night’s fight and today’s birds. “Even though it’s a competition, everyone gets along,” says Tonto, after greeting them.

Each weekend in Waianae, there are events called hacks, in which each entrant is allowed only one rooster. A hack can net a winning cocker $100 to $1,000. On average, Tonto says, he makes several hundred dollars during fights. The big money, he says, are the derbies: tournaments in which each fighter enters two to eight roosters. The cocker who has the most winning birds gets the pot money, $5,000 to $20,000, comprising the entry fees of each fighter. Winning fighters can also sell their birds. “I’ve been offered $500 apiece for mine. But they’re my personal birds. I don’t sell them.”

Dozens attend hack fights, while derbies attract hundreds, even 1,000 people. Virtually everyone there tries to make money. A din of voices erupts just before each fight as people place bets: Men, women, even teenagers yell out odds – “Jes” for the favorite, “Take jes” for the underdog, and “Even” for 50-50 odds. Like the house of a casino, the owner of a cock- fight always wins by taking a cut of the pot and admission fees. It’s $10 to watch a derby, says Tonto, plus another $20 for ringside seats. On an especially lucrative day, a ring owner can make up to $50,000.

After nearly five decades of fighting, Tonto says he’s still exhilarated walking into the ring. “I love the adrenalin rush. These birds are my pride and joy. Cockfighting helped get me through hard times. I had a rooster called Haole Boy. He was pure white. I had so much pride in my rooster. I took him from the breeding pen and then fought him for $500. I didn’t have one penny in my pocket. I told him, ‘Win,’ and he did.”

Sex Work in the Digital Age

Like many of his co-workers, Doug Upp embarked on one of his careers by happenstance. The Honolulu native was living in the Hollywood area in the early ’90s. He was skating downtown one day after his shift at Tower Records, when a man pulled alongside and propositioned him. “I said, ‘OK.’ It didn’t hurt, it actually felt good, and I walked away with some good money.”

Upp has been a sex worker since. Men will call or text him to set up “dates” with Upp and they’ll meet at hotels and, before it closed, at Max’s Gym, a bathhouse in Waikiki for gay men where Upp worked. “I also had a sugar daddy,” he says, a consensual arrangement in which he was a live-in companion with a prominent Honolulu business owner for about seven years.

Upp says he doesn’t have a rate card, a set hourly or nightly charge for clients, but that he usually goes home with $100 after each date. “One long-term client wanted the fantasy that he wasn’t paying me. There was no discussion of money; at the end, I’d get $100 as a tip for hanging out.”

A professional sex worker’s rates both in Honolulu and across the U.S. Mainland can vary from $100 to $1,000 a night, or $200 to $500 an hour. Upp says he’s also had clients buy him gifts, such as a digital camera.

Today Upp, in his mid- 40s, considers himself an occasional sex worker; he works part-time at a bakery and an adult store. He also performs in drag shows, trading in his usual look of graphic tees, pulled-back black hair and plastic-frame glasses for more upscale ensembles. In fact, he says, many people work in the industry part-time for extra income. “I’m opportunistic about it: If somebody offers it, I’ll say yes if I’m interested or if the money sounds right,” he says. “I’m pretty lucky and privileged being cis-male and light skinned. I speak English, I’m American, I’ve been outside of the country, I’ve been to college. I have all these things going for me. I’m in a situation where I don’t have to do it.”

Like Upp, Kimberlee also enjoys the freedom, pay and opportunities of being a sex worker; this is her 20th year in the industry. Kimberlee isn’t the red head’s real name; it’s the professional moniker she’s assumed. She started working in the legal sex work industry as an exotic dancer, both in California and Hawaii. “I came to Hawaii in 1998 and started dancing at the Crystal Palace,” she says of the popular Honolulu strip club, now closed. While she liked the work, she wasn’t fond of the management, so she became an escort in 2004.

Kimberlee, in her mid-30s and a mother, now lives in her native California again. “There’s less money in Hawaii. There’s a lot more business and political travel happening in California.” She advertises her services on select escort websites and meets her “dates” at her favored hotels. There are even Oahu men who request her services, occasionally booking her for three to five days, including travel expenses. “This is an industry in which repeat clientele is rewarded. There’s huge preferential treatment, often for safety reasons. I take them to the North Shore where we can relax,” Kimberlee says.

Kimberlee’s and Upp’s jobs require more than just being good at sex. “It’s a lot of emotional labor. People just want to talk,” says Upp, adding that he’s had dates where all they did was talk. “They need the companionship and intimacy they can’t find at home, they’re traveling or they’re in a closeted situation.” Kimberlee says she even took counseling courses to become more adept at communicating.

Today Kimberlee’s skills net her $35,000 to $45,000 each year. She says she made more when she was younger and childfree. Despite working in an industry where she’s paid in cash and doesn’t receive W2s or 1099s, she says, she files tax returns each spring with the IRS. No, she doesn’t list her occupation as sex worker, rather she files her income under entertainer. “For me, my tax reports are the only thing that demonstrate I have reliable income. That’s how I prove to banks that I’m a worthy debtor.”

Even though Upp’s and Kimberlee’s jobs aren’t regulated, their industries feed the legitimate economy: hotel stays, cab fares, airfare, meals, and clothing and sex toy purchases. “We contribute to the economy the whole time,” says Upp.

Kimberlee adds that she spends a lot of money and time maintaining her physical appearance for her job, including gym membership, trainer and regular spa and body treatments. “I’m going to the gym right after we’re done talking” Barefaced and sporting chunky glasses, she’s already wearing yoga pants and a loose T-shirt.

“We’re working hard to function as a visible and reciprocal part of the economy, but we’re being forced into the margins against our will. It’s not that we’re hiding out in the black market,” she says.

In Hawaii, prostitution and soliciting prostitution are both petty misdemeanors. In 2016, Honolulu police narcotics/vice officers made 93 arrests for prostitution and 87 for solicitation. Often, the risk of sexually transmitted diseases, assault or robbery outweigh the possibility of arrest for sex workers.

They also know the pervasive stigma attached to their jobs, including harassment and social isolation. “We need rights, not rescuing,” says Upp. It’s become a popular catchphrase within the community, he explains, because, while there are indeed people tracked into sex work, mostly women, the majority of sex workers are in the trade by choice.

That’s why both Upp and Kimberlee are advocates for sex-worker rights. Upp started an online zine and has participated in sex worker film festivals. His mom even knows he’s a sex worker, he adds. In 2005, Kimberlee co-founded the Desiree Alliance, a coalition for sex workers, health professionals, social scientists and educators to create better understanding of the U.S. sex-work industry. The two also work with Tracy Ryan, who founded the nonprofit Harm Reduction Hawaii and does advocacy and outreach with transgender sex workers. She’s also spearheading local escorts to pass a bill decriminalizing prostitution in Hawaii.

“I started doing all this because my transgender friends in the ’90s started doing sex work. It’s virtually impossible to make a determination on how many sex workers there are today … but if you compare today to the late ’80s and early ’90s, there are fewer women out there,” says Ryan, thanks to the popularity of online personals and escort websites. “I remember in the ’90s, you could stand on a corner in Waikiki and you’d see all these attractive women in 4-inch heels and designer clothes strutting around. Chinatown used to have 50 trans women who worked there as sex workers. That’s way down, too.”

Even if there are fewer women walking along Kuhio Avenue, sex work will always exist in Hawaii, powered by women and men like Kimberlee and Upp. “I don’t want to be in a corporate ( job). I want to work for a real person who I can trust,” says Upp. “It’s quick cash and, if you’re lucky, you get to make your own rules.”

Peddling Pakalolo on the Side

For years, whenever Damien was at a party, or cruising at a friend’s house, he’d always decline when he was offered pakalolo. But he saw a business opportunity in the dried, smokeable plant. “I thought I could make some money off of it just to get by. I started selling an eighth (of an ounce) and built up selling more and more from there,” says Damien, a Hawaii native who also works outdoors and plays in a local band. He started selling marijuana seven years ago and now smokes it, too. In addition to his income from dealing, he has the perk of free product.

“Marijuana is the most abused illicit drug in Hawaii,” says Gary Yabuta, the director of the Hawaii High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area, a federally funded agency that helps federal, state and local enforcement fight local drug trafficking. But despite this flourishing illegal economy, Yabuta says, the No. 1 drug concern in Hawaii is crystal meth- amphetamine, also known as ice, trafficked to Hawaii via cargo ship, postal service and human smugglers.

Damien can attest to the low status of marijuana on law enforcement’s priority list. “I’ve got into trouble before. But they just took (the marijuana) away. It was just a slap on the wrist,” and he wasn’t arrested, he says. “I think the police don’t consider it a heavy drug, unless it’s some kind of rookie cop, but undercover cops are just gonna take your stuff. If it was something else, I’d be going down for sure.”

That’s one reason he sells only marijuana, even though promoting and distributing it is a felony, as it is for methamphetamine, heroin, cocaine or morphine. (Still, Damien asked that Hawaii Business not use his real name in this story.) According to the Honolulu Police Department, 653 arrests were made for possession of drugs in 2016. To avoid arrest, or getting his merchandise confiscated, Damien contacts different distributors, who get marijuana from the Neighbor Islands or the West Coast. “We use code names, make quick calls, coded text messages,” he says.

He usually gets a half-pound or less of marijuana about once a week. He pays his suppliers cash upfront, then resells the marijuana, netting $250 each month. “I’m not a big time dealer. I don’t want that weight on my shoulders.”

Most of his customers purchase one-eighth of an ounce, which he sells for $50. He sells to 10 to 20 regulars, including friends, who then give some to their friends. “It’s more iffy if it’s a stranger. I ask them if they’re a cop, and usually it’s alright.”

He has a variety of customers. “Some have kids, some use it medicinally, some use it for stress relief. Some just buy to take one hit once in a while.” And even though he knows most of his buyers, Damien says he doesn’t sell from his home or work, but at discreet meeting spots. “It’s safer that way.”

Damien has been following the news about Hawaii’s medical marijuana dispensaries. He says he doesn’t think he’ll lose his customers when the legal local medical marijuana shops open. “My customers aren’t (medical marijuana) card holders,” he says, adding that none have expressed interest in registering.

Like many people who use marijuana, he thinks it should be decriminalized. “I don’t consider it a drug. It’s healing. Even though it is illegal, I’m helping people, not getting them into any heavy drugs. You can’t overdose on it. If anything, you’ll just fall asleep.”

$53 BILLION INDUSTRY

Most Americans and Canadians get their marijuana from black-market dealers like Damien, even as the industry continues to transition from illicit to legal retailing, according to ArcView Market Research, a leading marijuana industry investment and research firm.

In 2016, marijuana sales in North America raked in $53 billion; 87 percent, or $46 billion, were from the black market, ArcView estimated.

THE PRICE OF ICE

As with legitimate markets, the law of supply and demand plays a huge role in black markets. For instance, the Hawaii High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area estimates these black-market prices for one kilogram (2.2 pounds) of crystal methamphetamine:

- Los Angeles: $6,000

- Honolulu: $30,000

One factor is that Los Angeles is little more than a two-hour drive from Mexico, a major source of the illegal drug. Supplying Honolulu is much more diffcult, because the drug must be smuggled by air or sea over thousands of miles.

The Gray Economy

Whether it’s $100 to bet on a cockfight, pay for sex or buy pakalolo, each act operates in the black market. But there are many other ways to contribute to the underground economy: hiring an unlicensed contractor to repair your home, paying cash for a better price on a car detailing, or renting your spare bedroom and not reporting the income.

Cash payments aren’t illegal, but businesses – both legitimate and illegitimate – often use them to avoid reporting taxable income. The Hawaii Department of Taxation estimates the state loses $1 billion annually in uncollected taxes because of unreported income.