From our Old Bike Archives – Issue 74 – first published in 2018.

Story: Jim Scaysbrook • Photos: Ray Goulter and Jim Scaysbrook

According to definition, a sunbeam is a delicate shaft of light, and while the term ‘delicate’ may well be applied to the pre-WW2 offerings from the Wolverhampton-based company, it is not a descriptive that springs to mind for the in-line twins that appeared post-war following Sunbeam’s takeover by BSA. In fact, the pre and post-war offerings were poles apart. On one hand, lithe sporting singles possessed of a healthy turn of speed and sublime handling, and on the other, rather bloated and underpowered. Yet the Sunbeam S7 was in in principle at least, exactly what the British motorcycle industry desperately needed to embrace – fresh thinking.

Sunbeam itself had a chequered history, beginning in 1899 as the product of John Marston Ltd. The first powered Sunbeam was a strange looking four-wheeler with a single wheel front and rear and wheels at each side – often described as a ‘sofa on wheels’. Subsequent Sunbeam cars were far more elegant, and this side of the business was split to become the Sunbeam Motor Car Company which produced a line of highly acclaimed vehicles. The original concern continued as a manufacturer of pedal-powered bicycles, uniquely fitted with a fully enclosed oil bath rear chain – a feature carried over to the first Sunbeam motorcycle, the Gentleman’s Motor Bicycle, which appeared in 1912. A 350cc single with a two-speed countershaft gearbox and multi-plate clutch, the new Sunbeam was a quality item, with a rear-mounted Bosch magneto and eccentric flywheels to achieve crankshaft balance. The impeccable finish became a signature of subsequent Sunbeams, with deep black enamel finish and genuine gold leaf lettering and lining.

Having survived WW1, Sunbeam was struck a crippling blow when John Marston died in 1918 aged 82, followed less than a year later by his son Roland. The company soon had new owners, Noble Industries, which itself later became the giant Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI). Under the new ownership, Sunbeam flourished, with competition successes that included Isle of Man TT victories. New 350 and 500cc overhead valve engines were immediately fruitful, and the company recruited Graeme Walker (father of Murray) as Competitions Manager and works rider. Grand Prix and further TT wins followed, but so did the Depression, and the Sunbeam range was trimmed to just four models. Unlike many of its competitors, Sunbeam saw out the crisis, but in 1936 ICI sold Sunbeam to London-based Matchless, who already owned AJS, to form a new company called Associated Motor Cycles Ltd (AMC).

For a year or so, little changed in the Sunbeam line up, but then came a completely redesigned model, known as the High Cam, which was not in keeping with the svelte and sporty models of the past. Production of the new line had barely started when Britain once again found itself at war. Almost covertly, as the war drifted towards its conclusion, AMC quietly divested itself of the Sunbeam brand, which now became part of BSA in Birmingham in 1943.

It could have been expected that BSA, having acquired the tooling as well as the naming rights, would simply continue where AMC had left off, but what appeared as the next chapter in Sunbeam’s history owed nothing to what had preceded it. What BSA envisaged was a luxury machine with a completely unique specification, and to achieve this BSA hired a designer from outside the mainstream motorcycle industry; Austrian-born Erling Poppe, who had previously been a designer at the bus-building division of British Tramways and would later become chief design engineer at Rover cars. Earlier in his career, Poppe had been a partner in Packman & Poppe, producing a 250cc two stroke utility motorcycle and later a 976cc side-valve JAP-engined model, but he had been away from the motorcycle scene for more than 20 years when he arrived at BSA.

Although the BSA board placed several stipulations in regard to their new Sunbeam model (including that the performance should match the Triumph twin, and ‘must not incorporate BSA features that could be recognised’), Poppe was not given carte blanche when it came to the design of the new 500 twin, which was in fact projected to be the first of a line of similar designs that would include a 300cc version. Instead, Poppe was given the design of a BSA prototype from the ‘thirties which had failed to proceed to production, the Line-Ahead Twin. His stay at BSA was brief, and the final touches to the new Sunbeam were entrusted to Gerry Bayliss.

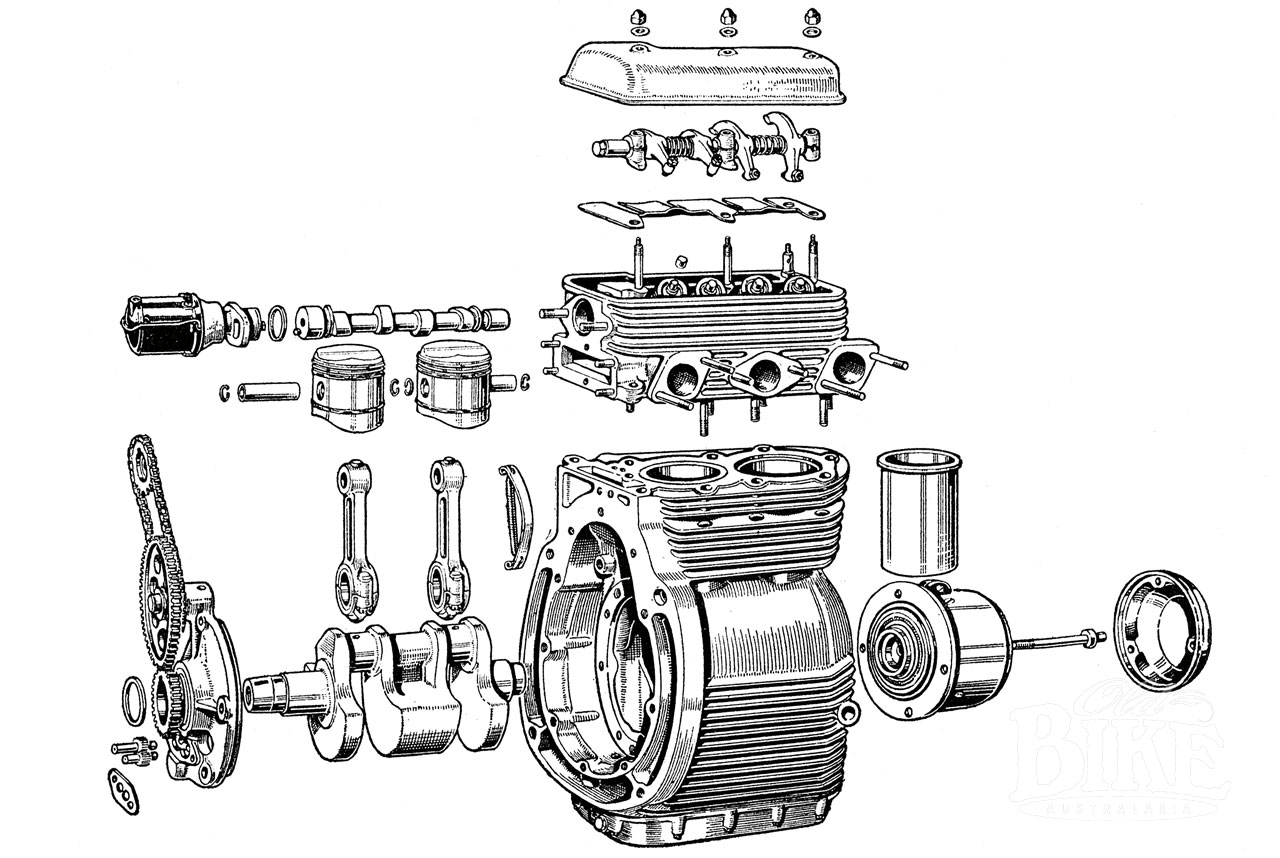

Designated the S7, prototypes of the new model were built in two forms; a touring version and a sports version, the latter of which never reached production. Poppe brought much car-based thinking to the drawing board, seeking a clean, smooth-running, quiet and easy-to-start machine. The engine itself, with its unit four-speed gearbox, was an all-alloy, wet sump parallel twin with the crankshaft set along the frame and horizontally-split crankcases, with the top half incorporating the cylinder block. Oil was contained in a cast-aluminium sump bolted to the lower face of the crankcase. The first cylinder head produced was a cross-flow design, with the carburettor on the left. The combustion chambers were of the squish type, and the engine, in production form, was efficient and reasonably powerful. Final production heads had the inlet port and carburettor switched to the right side, sitting between the exhaust ports.

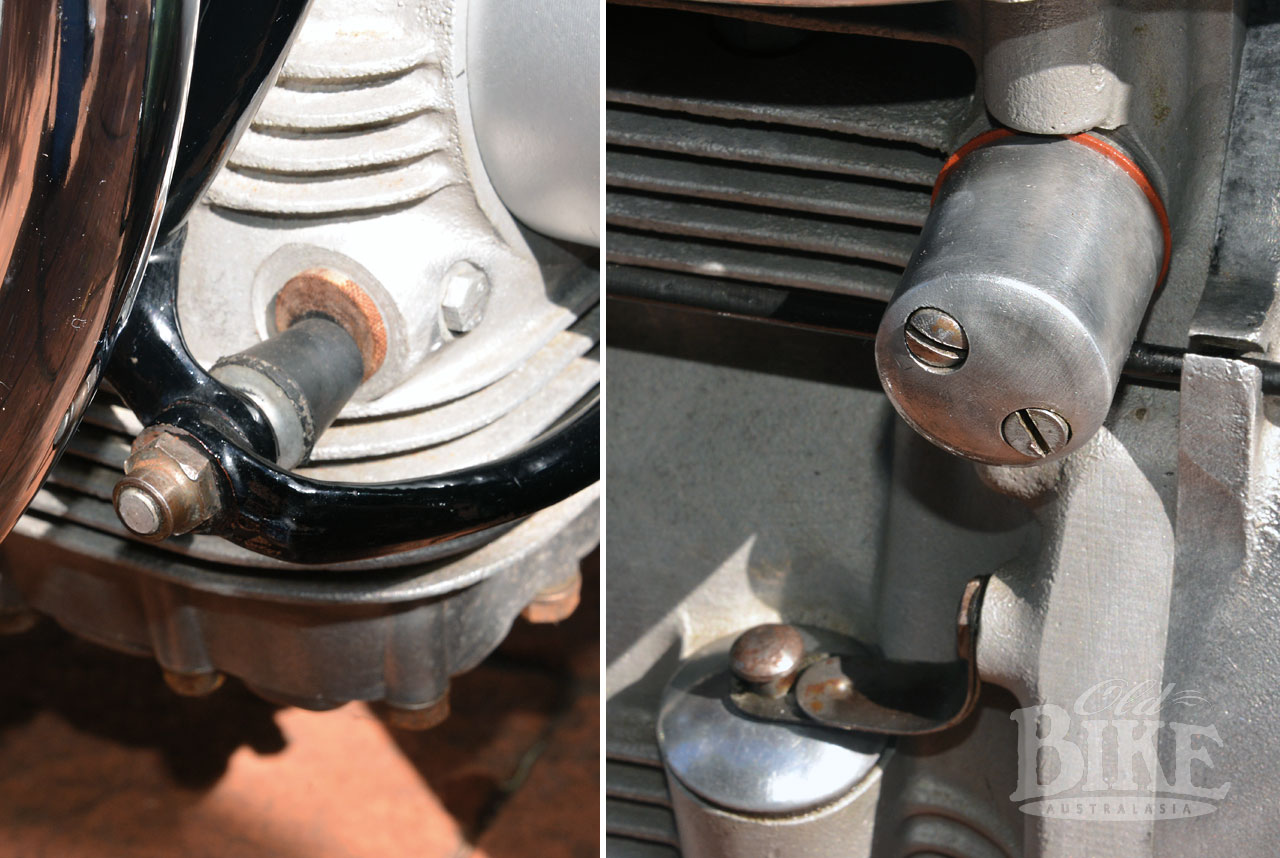

The valves were operated by a chain-driven single overhead camshaft, and final drive was by shaft. To reduce the inherent mechanical noise of an all-alloy air-cooled engine, short, stiff fins were cast, and the camshaft fitted with quietening ramps to provide a slow transition for an 18-thou tappet clearance. The design team believed that the elimination of pushrods in favour of the overhead camshaft would also lower mechanical noise, and also allow the use of lighter valve springs, which in turn produced less wear on valve seats and further reduced noise. The choice of a chain rather than a vertical shaft to drive the camshaft was also done for noise reasons. The cylinder head used a single inlet port with an Amal Type 275 carburettor with a tiny 15/16” choke size, and twin exhaust ports. A Vokes oil-drip air filter was housed in a swish looking shroud, held in place by three acorn nuts. On the opposite side of the head, a cast-alloy streamlined and finned cover kept the weather away from the spark plugs.

At 70mm x 63.5mm, the engine was well over-square, and used very short light alloy bolted-up con-rods to keep piston speed down and ensure the engine was as compact as possible. Each Y-alloy piston used four rings; two compression rings and an oil ring above the gudgeon pin, and another oil ring at the base of the skirt. The one-piece iron crankshaft had a very large central bob-weight, supported at the front by a ball bearing and at the rear by a plain, white-metal lined bearing with a spring-loaded oil seal to prevent engine oil from reaching the clutch. The clutch used a single seven-inch plate, car-style, operating directly onto the flywheel.

Ignition was by battery and coil, with an automatic advance and a distributor driven at half engine speed from the rear end of the camshaft. Power was supplied by a 40-watt Lucas dynamo with the armature carried on the front end of the crankshaft where it received a direct stream of cooling air.

The cradle frame had widely spaced front tubes that were bolted to the front of the crankcase, with telescopic forks at the front and plunger rear suspension. Defying conventional logic and perhaps with a tilt to the US market, fat 4.50 x 16 front and 4.75 x 16 rear tyres were fitted. Although conventional in appearance, the front fork was a bespoke item with no internal damping for the legs. Instead, the tubes contained oil-soaked cotton for lubrication with rubber bump-stops for the sliders. A speedo was located in the headlamp to the right hand side, with a pair of warning lights on the left; red for ignition and green for oil, the latter blinking if the oil level fell below one pint.

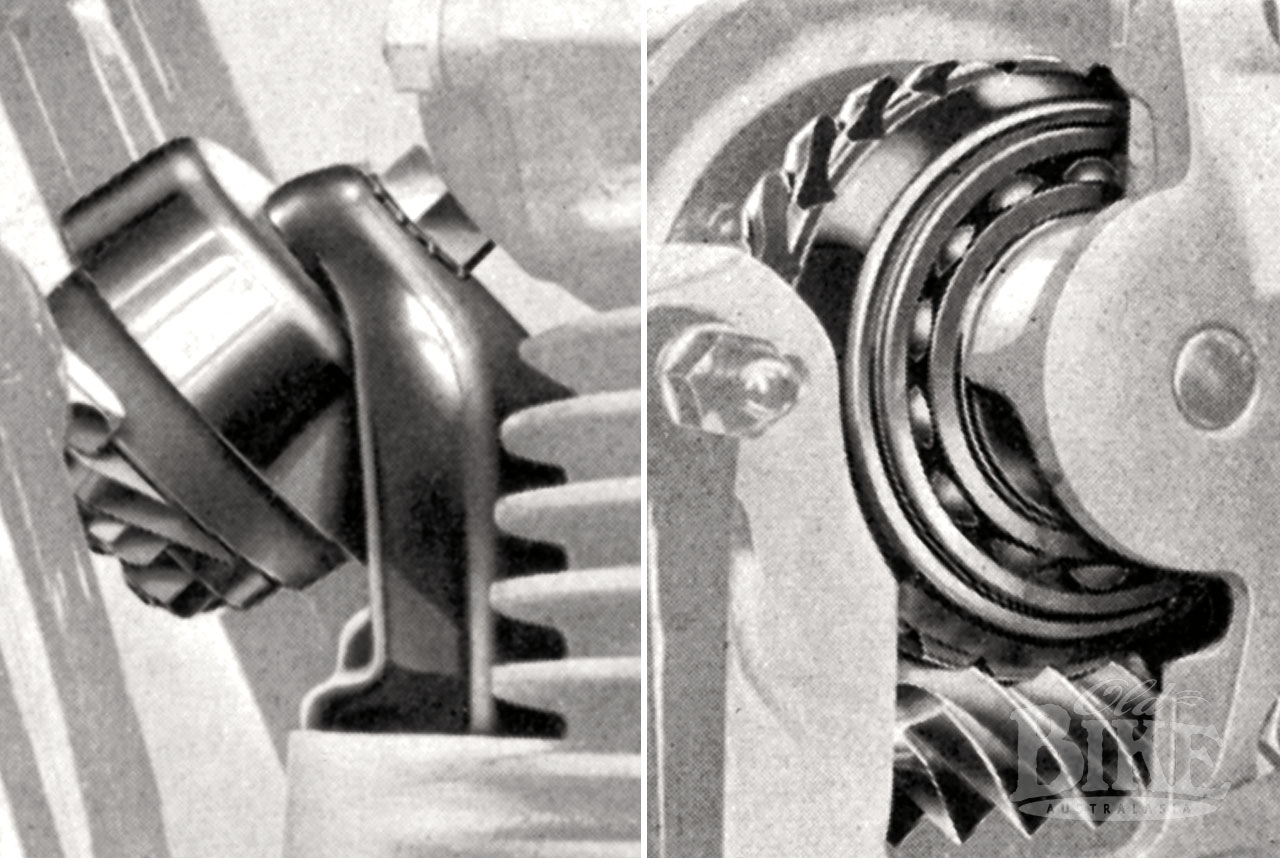

The final drive shaft had universal joints front (a rubber Layrub coupling) and rear (a Hardy Spicer metal unit) that ran at approximately half engine speed in top gear. However instead of the bevel crown wheel and pinion used by others including BMW and Zundapp, BSA stipulated the use of worm and wheel drive gears, probably because these were a stock item used in another BSA product – Daimler cars. This component proved to be the Achilles Heel of the entire design, although when properly set up with shims and matching components, plus the correct grade of lubricant, can give long trouble-free service.

By 1945, the prototype S7 was ready for testing, but the unfortunate chaps to whom that task fell reported that the vibration from the engine, which was rigidly mounted in the frame, was so severe that it was all-but unrideable. Even with this fault, the first batch of S7s was built in 1946 with the engines secured directly to the frame, but all were recalled for modification. In a very embarrassing episode for the brand, a small batch of S7s from the first production run was rushed to South Africa to act as escort vehicles during the visit of King George VI, but the riders complained so vehemently of the vibration they were withdrawn and sent back to the factory. The fix was in the form of isolating the engine from the frame by a series of elastic mounts. The low-frequency vibration was absorbed by two diagonally-disposed, bonded rubber engine mountings. To absorb half-frequency vibration, caused mainly by the motion of the con-rods, a spring-loaded friction damper was mounted at the top (rear) of the engine. What BSA/Sunbeam called “snubbers” – small rubber buffers carried at the top (rear) and bottom (front) of the engine – controlled oscillation. The engine still danced around, but at least the effect was no longer transferred to the rider. To prevent the exhaust system from breaking up under the vibration, a short length of flexible metallic tubing was used to couple the pipes.

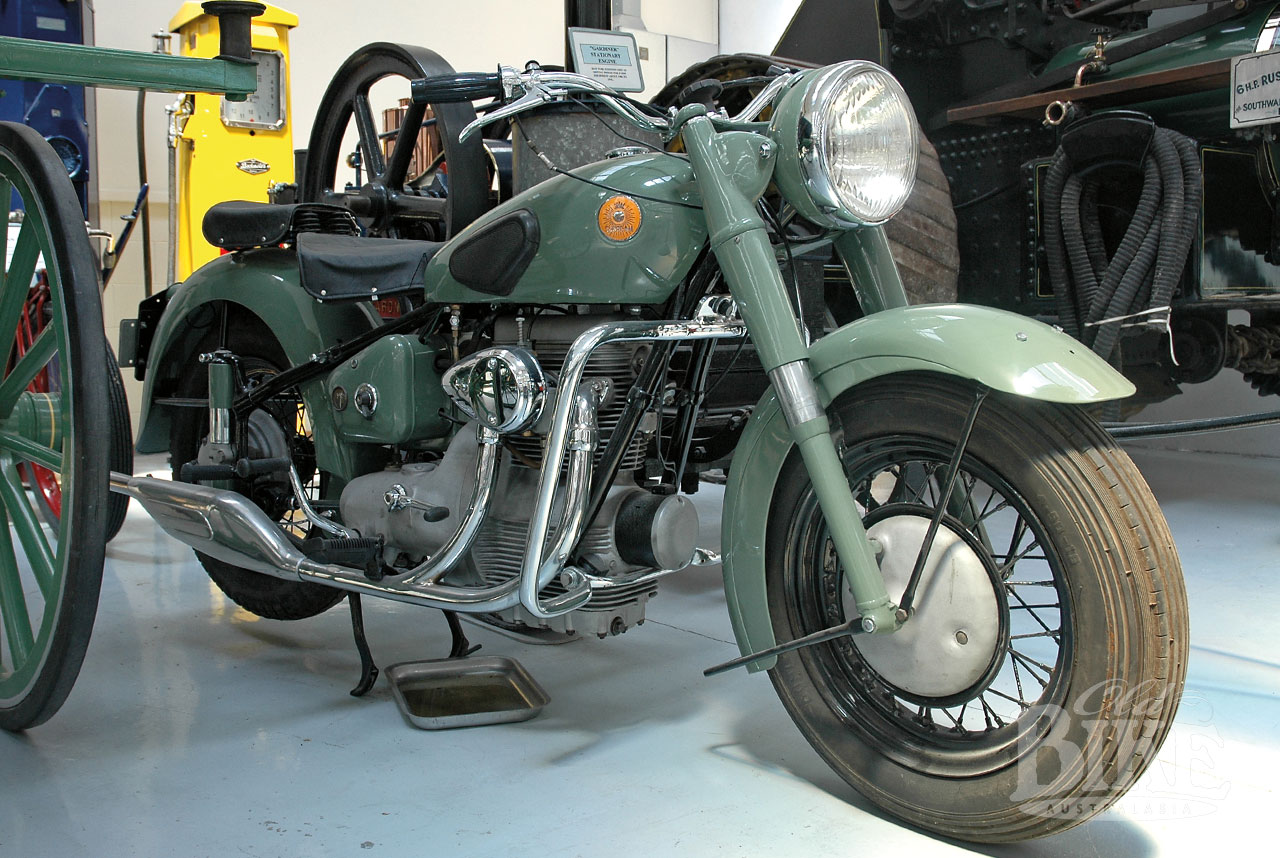

Initially the S7 was available only in black, but a Mist Green option was soon introduced. When the S7 went on sale in 1947 it carried a substantial price tag – £222 (Including UK purchase tax) when the company’s own BSA 500cc A7 twin sold for just £167. As feedback from initial sales drifted in, a common problem was highlighted; that the final drive set up chopped out after as few as 5,000 miles. Unless meticulously set up, the worm-drive to the rear wheel was incapable of transmitting the power of the engine, and the gearbox casing also grew extremely hot after a decent run, so company’s answer was not to redesign the final drive componentry, but to de-tune the engine to produce something like 24hp.

The un-damped front forks soon gained single-way damping, which improved ride quality considerably, and numerous other detailed changes made to the S7, such as replacing the original inverted front brake and clutch levers (which pivoted from the ends of the rubber-mounted handlebars in true vintage style and had their cables running inside the bars), with conventional levers and exposed cables. A new model, marketed as the S7 De Luxe was shown at the first post-war motorcycle show in England, held at Earls Court, London in November 1948.

Also displayed at this show was a second version, called the S8, available in black or polychromatic grey, with a cheaper price and 12kg less weight, which gave it better performance. The S8 differed in many ways, including a revised oiling system with a larger capacity, but visually the main change was the reversion to conventional 19-inch front and 18 inch rear wheels and tyres, narrower section mudguards and lighter front forks and a smaller front brake sourced from the BSA twin. The S8 also had a conventional sprung saddle instead of the Terry cantilever type on the S7. In place of the S7’s tubular steel silencer, a cast aluminium version was used. In both the S7 de Luxe and the S8, engine power was increased slightly to 26hp.

The S8 went on sale in 1949 but although the S7 continued alongside it until production ceased in late 1956, neither ever sold in acceptable quantities, although BSA announced in November 1951 that the 10,000th Sunbeam twin had just rolled off the production line. Six years later, this figure had increased by just over 6,000. The official production figures are 7,658 for the S7 and S7 de Luxe, and 8,530 for the S8. A major factor in this lack of showroom success was undoubtedly the price, which by 1950 had risen to £259 for the S7 and £227 for the S8, when a 500cc Royal Enfield twin went for £177 and the A7 BSA twin for £182. But there was also the matter of styling, which was a ‘love it’ or ‘hate it’ situation with buyers. Another factor was the rather underwhelming performance, which could only be rectified by a complete redesign of the transmission. Both the S7 and S8 had been built to the highest standards of finish and appointment, and BSA felt there was no point in compromising this by lowering specifications to achieve a lower retail price. And so after a little more than a decade in production, one of the most innovative post-war British designs slipped into oblivion.

For all its quirks, Sunbeam S7/8 owners universally praise the smoothness of the riding experience, which is a far cry from the hippy-hippy shake of the first batch. Today, examples of the Sunbeam twin – universally referred to as “The Gentleman’s Motorcycle” since its inception – are highly prized, and the long-established Stewart Engineering in UK does a worldwide trade in new and second hand S7 and S8 parts.

Thanks here to Bryan Fowler (British born, raised in USA, and for the past decade, a Sydney resident) for the opportunity to photograph his 1953 S7 De Luxe. Among several others, Bryan has three motorcycles that he believes were significant turning points in the post-war British motorcycle industry; the S7, a Velocette LE, and an Ariel Leader. I think he is quite correct when he says that this trio embodied very fresh thinking – a deliberate move to break away from the traditional and tired designs that had become entrenched in the industry. His S7 was purchased from Kohl’s in Lockport, New York (see Bryan’s story in OBA 72 Out & About). “I bought it in 1982,” says Bryan, “after looking at it sitting on the shop floor since 1977. I also rebuilt one last year that I bought in Newcastle, NSW. These bikes have lots of traps for would-be restorers; left thread axles, hidden nuts in the cylinder heads; people miss these and try to lever heads off. I have had BMWs (and still ride one) but the S7 is one of the smoothest bikes I’ve ever ridden. This one has the Mk2 front forks, which are much better. They absolutely must have metal fuel lines or they melt on the exhaust pipes and the bike can catch fire. The dipsticks used to blow out with crankcase pressure, so they were redesigned with a securing clip. On the early engines the cylinder sleeves were not pinned and tended to work loose, so the later ones were pinned.”

With assistance from his wife Zac, who tolerates such marriage-testing stunts such as cleaning motorcycle parts in the dishwasher, Bryan has restored all his bikes himself, as he explains. “All the work done on the S7, LE and Ariel (excluding engine machining and chroming) I did myself (with the bride assisting with critiquing or sewing pannier inserts). I am saying this, not for self- aggrandisement, rather, too often, restoring something becomes a question of who’s got the biggest cheque book, which I resent. I would like others to know, who may just be getting interested or started in restoring things, to be willing to give it a go. I have no formal training, but I quickly learned, to keep your ears and eyes open to the old timers… and the wonders of a Hills Hoist clothes line – par excellence for hanging motorcycle parts, to then, paint them, or an extension ladder set between two trees. Thankfully the bride understood early in the game, the kitchen is a manufacturing centre…as such…the dishwasher is unbeatable for final cleaning of parts, stove-paint using the oven, etc, and for anything too big to wash there’s the bathtub!”

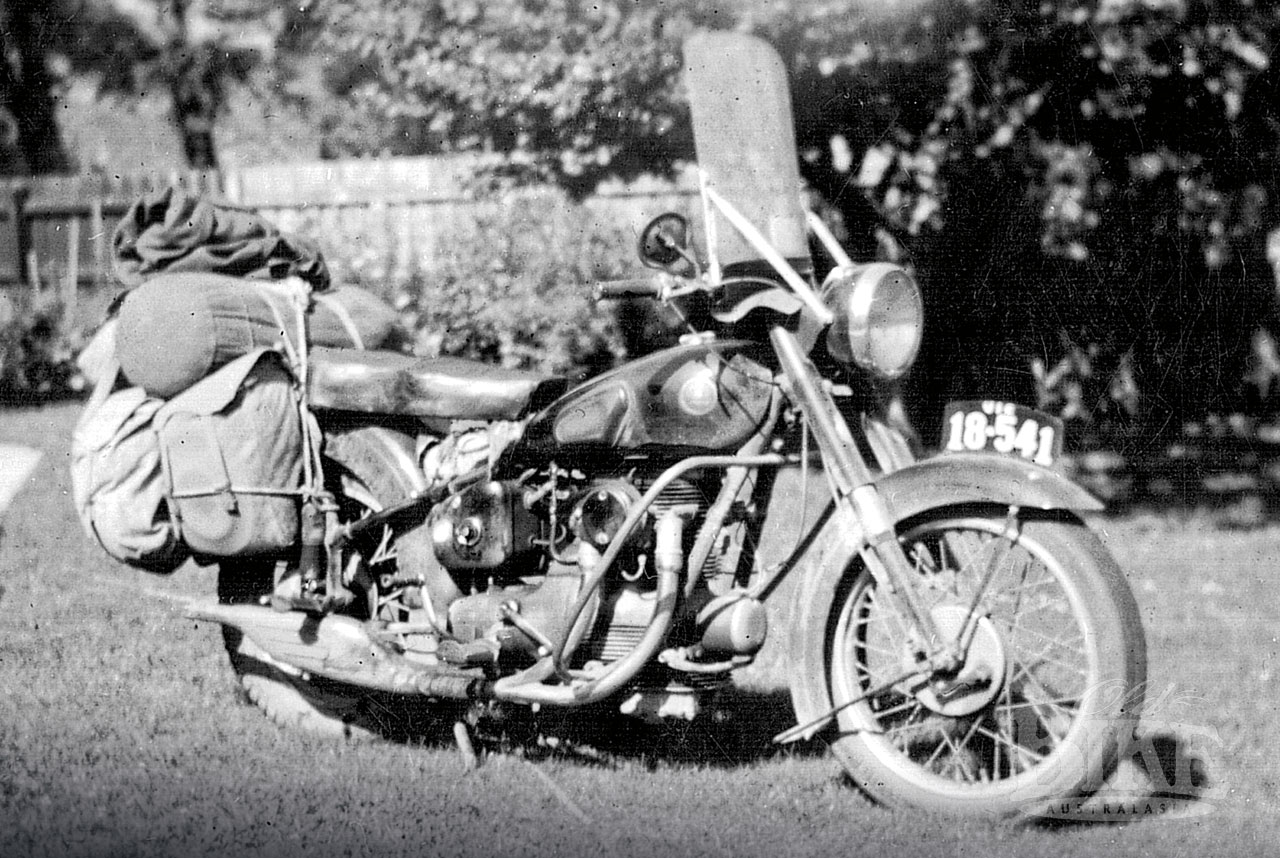

The S8 featured here belongs to South Australian John Watson. Ray Goulter, former secretary of the Auto Cycle Union of NSW, photographed the bike at John’s home.

Specifications: 1947 Sunbeam S7

Engine: Twin-cylinder OHC air cooled.

Bore x stroke: 70mm x 63.5 mm

Capacity: 487cc

Compression ratio: 6.8:1

Power: 26hp at 5,800 rpm.

Ignition: Coil and battery with auto-advance.

Lighting: Lucas 8” headlamp

Gearbox: Sunbeam four speed.

Final drive: Shaft and underslung worm.

Suspension: Telescopic front fork, plunger rear.

Tyres: 4.50 x 16 front, 4.75 x 16 rear.

Wheelbase: 1448mm

Weight: 195 kg

Fuel capacity: 16 litres

Top speed: 75 mph (120 km/h)